My

desire to hunt and the resultant conservation benefits are not mutually

exclusive; they are actually inextricably linked. The net conservation benefit

has nothing to do with why I hunt, however these benefits are very

positive by-products of my hunting, a convenient truth. There will be some

greater good because of my quest to hunt the world's largest land animal.

So

what could lead to a need to kill elephant and how could such action possibly

have a positive outcome? Well there are a few things, and while we can

list them out for discussion, in reality they are intertwined in such a way

that each is a contributing factor to the other:

- Increasing populations;

- Boundaries in the modern world;

- Carrying capacity.

Increasing

populations

Successful

management of wildlife must be linked to the welfare of local communities. To

look after the people, the wildlife must be managed, and to assure the future

of Africa's mega fauna the needs of the communities that share their range must

be considered.

In

1950 the average family group in rural southern Africa had enough land to grow

more than enough food for themselves and were able to sell some of their

harvest to procure the things they couldn't produce. The typical piece of land

we’re talking about supported 8 people.

Animals

that roamed freely would come into contact with humans, particularly along the

edges of parks and reserves, but the conflicts were limited and fatalities on

both sides reflected that. Opportunistic elephant would raid crops but the

situation was tolerable.

In

2010, that same piece of land is supporting 60 people, with a documented

doubling of the population every 20 years. That same piece of land is now under

immense pressure in terms of food production.

As

the intrinsic poverty of a community increases, the people will do whatever is

necessary to ensure that their basic needs are met. Killing animals for

meat puts food in people’s bellies. Killing elephant and rhino for ivory

and horn puts cash in people’s pockets – typically the ivory from an elephant

may put USD30.00 into the hands of a poacher. Yes, that’s thirty dollars.

Following

the ban on the ivory trade by the parties to the CITES Convention, the elephant

population has enjoyed a consistent growth of 5% per annum and today their

numbers are at their highest in modern history in spite of the terrible

poaching we saw in the '70s and '80s.

|

| A consistent population growth of 5% per annum has seen elephant number reach all time highs in southern Africa. |

The tension between humans and wildlife is at an all time high in

wilderness areas all over the world. Human-animal conflict has reached

unprecedented levels for elephants in both Africa and India.

Humans are struggling to produce enough to feed themselves - the

impending global food shortage has made mainstream news quite a lot in recent

times - and elephants in unusually high numbers find the various fruit and

vegetable production areas irresistible. These small agricultural enterprises

have become a hot zone of human-animal conflict and whether it be crop raiding

elephants, predators preying on cattle and goats or attacks on people, there is

considerable resentment from rural African communities towards wildlife.

These feelings do not bode well for Africa's big game and without

creating some intrinsic value to the people; the future for wildlife may have

been bleak.

|

| The abbatoir in Kruger Park processed meat resulting from culls. |

We’ve

created countries and provinces with cities and towns and highways. The great

migrations of yesteryear are more and more limited as humans prosper and

increase their range. With the increase in population comes the need for

greater infrastructure and employment and the much more complex systems

required in our modern lives.

Extensive

road networks and highways, railway lines for passengers and freight, growing

cities and suburbs, an ever increasing number of rural villages and more

agricultural activity at a larger scale than ever means that there is huge land

pressure in modern Africa.

As

humans encroach further on African wilderness areas, much of the wildlife in

these areas finds itself as either a victim of the illegal bush meat trade or

in the case of mega fauna and predators, in conflict with local communities and

their agricultural activities.

Cropping

activities are producing a far more palatable and nutritious food source than

is generally available on the edge of what may be very poor country or an

ecosystem that is failing under the burden of mouths to feed. So a crop, be it

onions or orchards is going to be a hotspot for elephant activity.

Whilst

raising livestock is an issue due to predators, there is a less obvious

connection with elephant. The Masai in Kenya, particularly around Amboseli

National Park are in constant conflict with lions but seemingly live in harmony

with the elephant; so localised land use also impacts the extent of human-animal

encounters and conflicts. In the northern reaches of South Africa along

the banks of the Limpopo River, elephants cross the riverine border from

Botswana and head south as they always have – but today they encounter

communities and agricultural activities that weren’t there before…

Carrying

capacity

Modern

man has done a lot of research into the carrying capacity of any given piece of

land to maintain a population of animals. In Australia, agricultural efficiency

has borne the concept of the dry sheep equivalent (DSE) where a parcel of land

is given a DSE value that indicates its sheep carrying capacity.

We

often struggle to do the same with our wildlife. The introduction of

significantly more watering points and improved pasture has given Australia’s

kangaroo species the opportunity to flourish in what is some of the most arid

country on earth. As a result large numbers of kangaroos are culled every year

under kill only or harvester tags.

I

have visited properties and had some involvement with culling operations where

kangaroos have been in plague proportions; swing the big Lightforce around the

paddock and you're met with hundreds of pairs of hungry eyes. It's worse when

conditions are poor and the mobs come out of the timbered country.

Although

not popular policy, the culling if kangaroos had been deemed necessary to

ensure good land management; left unchecked the kangaroo population would

implode, and in the short term, take our grazing industry along with it. At the

peak of our most recent drought in the summer of 2005 the bodies of 'roos, emus

and goats littered the paddocks as poor conditions and out of control animal

populations came to a head.

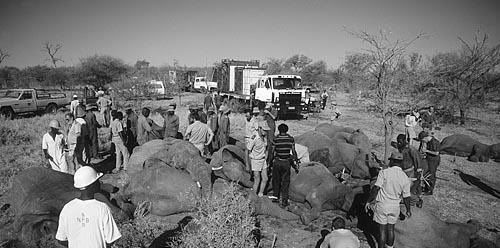

|

| After the choppers and shooters finish their job, the hard work resulting from the elephant cull begins. |

In

Africa the elephant is in a similar conundrum. By the late eighties numbers had

been decimated due to ivory poaching, however when the poaching was stopped

through the ban on international ivory trade and harsh anti poaching efforts on

the ground, populations soon bounced back to today's record numbers.

Botswana's

estimated carrying capacity is some 5,000 elephant for the entire country - the

near 200,000 elephant roaming the country have stripped the woodlands and the

famous Chobe River is slowly failing as its banks, stripped of all vegetation,

are eroded into the flowing waters. Beautiful as it is, Botswana is an

environmental disaster.

Similarly

Kruger Park has an estimated carrying capacity of 4,000 elephant. Today's

population is at 16,000 elephant and climbing in this relatively small area and

95% of the top canopy trees have disappeared since 1960 as a result of this

gross overpopulation.

So

what does this all mean?

And

so we come to those heated discussions in bars and at dinner parties.

Emotion charged and nonsensical arguments against the killing of elephant for

any reason, with trophy hunting being a particularly abhorrent concept.

Most

of those opposed to the killing of elephant would revert back to "…let

nature take its course, elephants did just fine long before we got involved…"

People simply need to understand that those days are gone forever.

A

number of factors have been highlighted to explain the need for effective

wildlife management: Africa’s massive human population, elephant numbers at a

record high (and growing), limited opportunity for the movement of big game

across the continent - more so as time goes by - and a grossly unbalance

elephant population, far in excess of the carrying capacity of the land.

We

have forever altered the face of the earth and created an environment where the

majestic elephant, once free to migrate thousands of kilometres as food sources

were depleted, are confined to areas that can no longer support a population

that grows at current rates. Allowing "nature to take its course" in

these relatively small, isolated game reserves and national parks will have

devastating effects on not only the elephant population, but on all wildlife

populations within each biome. As we lose our trees so we will lose the

wildlife that depends on them and in the ever-decreasing spiral we will devalue

the soil and limit its future potential.

The

interactions and options for today’s elephants, the communities live in their

range and the land that they share are somewhat limited. Unchecked, elephants

will continue to strip their habitat, the human-animal conflict will continue

as the elephants continue to raid crops and compete for the limited resources

available and combined, all of these factors will increase poverty and lead to

more and more illegal poaching to provide food and a source of income to

communities under pressure.

Two

things need to be altered in order to make significant change to this system:

- Reduce the elephant population to reduce the pressure on their habitat, reduce demand on resources and reduce conflict where elephants enter agricultural zones; and

- Empower the communities who share their range and give them control with some guidance of the renewal resources that they must share their lives with, provide people with enough food to eliminate any need for illegal activity to feed their families and provide these people with an income so that they may gain some independence and better their situation now and for future generations.

Reducing

elephant populations to suit the carrying capacity of the land can do all of

this. Culling of elephants will have the most impact on the total population in

the shortest period of time and meets many of the requirements I noted above.

Although unpalatable to many, culling at a rate equivalent to the natural

attrition rate would save the habitat and provide vast amounts of meat to feed

starving communities.

Hunting

on the other hand has less impact on elephant numbers in the short term with

arguably a more favourable outcome. As with culling, elephant numbers

would be reduced and with that come all of the resultant benefits; clearly a

combined hunting and culling strategy would be more effective in this regard.

Hunting would also provide meat. The great benefit of hunting are the

large sums of cash that may be provided to communities in the concessions where

the hunting takes place.

Granting people control over their resources makes wildlife valuable to

local communities because they can see an economic and ecological return.

Communities empowered with the right to control natural resources may choose to

sell hunting concessions to private operators under rules and hunting quotas

established in consultation with the wildlife department. Income is

generated through hunting lease fees, daily rates, trophy fees, and sales

of ivory, horn, skins and meat.

Communities can receive the benefits of hunting on their concession and

distribute a portion of the monies to each household as a dividend, and keep

the balance to fund community programs to create employment, provide healthcare

and education or other relevant projects.

Notice that I didn’t say trophy hunting in that last spiel; reason being

that there is a place for non-trophy elephant hunt purely for the purpose of

reducing numbers and providing meat. While a sport hunter may not be

willing to pay the same amount for a tuskless cow, there is still plenty of

interest in such hunts and an opportunity to generate income.

|

| This community live in a Big 5 hunting concession along the Kana River in Gwayi, Zimbabawe. I just provided a buffalo; the larder is full for now... |

And

ultimately, what is the point of all of this rambling? Those who live and

suffer the cost socially and economically and have the responsibility of

preserving as well as managing the natural resource concerned should receive

all potential benefits from the sustainable utilisation of that natural

resource.

To

this end, if hunters can get out there and enjoy the adventure of tracking and

stalking elephant, why not?

No comments:

Post a Comment